Quoted from: https://web.archive.org/web/20160417030218/http://ect.bell-labs.com/who/tkh/publications/papers/odt.pdf

Preliminaries: decision tree learning

Decision trees are a popular method for various machine learning tasks. Tree learning "come[s] closest to meeting the requirements for serving as an off-the-shelf procedure for data mining", say Hastie et al., "because it is invariant under scaling and various other transformations of feature values, is robust to inclusion of irrelevant features, and produces inspectable models. However, they are seldom accurate".

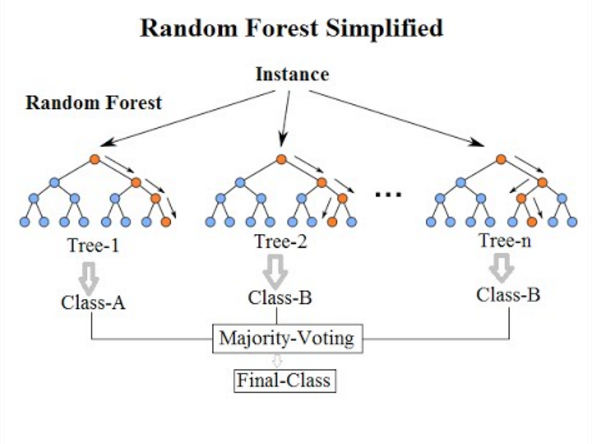

In particular, trees that are grown very deep tend to learn highly irregular patterns: they overfit their training sets, i.e. have low bias, but very high variance. Random forests are a way of averaging multiple deep decision trees, trained on different parts of the same training set, with the goal of reducing the variance. This comes at the expense of a small increase in the bias and some loss of interpretability, but generally greatly boosts the performance in the final model.

Forests are like the pulling together of decision tree algorithm efforts. Taking the teamwork of many trees thus improving the performance of a single random tree. Though not quite similar, forests give the effects of a K-fold cross validation.

Bagging

The training algorithm for random forests applies the general technique of bootstrap aggregating, or bagging, to tree learners. Given a training set X = x1, ..., xn with responses Y = y1, ..., yn, bagging repeatedly (B times) selects a random sample with replacement of the training set and fits trees to these samples:

- For b = 1, ..., B:

- Sample, with replacement, n training examples from X, Y; call these Xb, Yb.

- Train a classification or regression tree fb on Xb, Yb.

After training, predictions for unseen samples x' can be made by averaging the predictions from all the individual regression trees on x':

- {\displaystyle {\hat {f}}={\frac {1}{B}}\sum _{b=1}^{B}f_{b}(x')}

or by taking the majority vote in the case of classification trees.

This bootstrapping procedure leads to better model performance because it decreases the variance of the model, without increasing the bias. This means that while the predictions of a single tree are highly sensitive to noise in its training set, the average of many trees is not, as long as the trees are not correlated. Simply training many trees on a single training set would give strongly correlated trees (or even the same tree many times, if the training algorithm is deterministic); bootstrap sampling is a way of de-correlating the trees by showing them different training sets.

Additionally, an estimate of the uncertainty of the prediction can be made as the standard deviation of the predictions from all the individual regression trees on x':

- {\displaystyle \sigma ={\sqrt {\frac {\sum _{b=1}^{B}(f_{b}(x')-{\hat {f}})^{2}}{B-1}}}.}

The number of samples/trees, B, is a free parameter. Typically, a few hundred to several thousand trees are used, depending on the size and nature of the training set. An optimal number of trees B can be found using cross-validation, or by observing the out-of-bag error: the mean prediction error on each training sample xᵢ, using only the trees that did not have xᵢ in their bootstrap sample. The training and test error tend to level off after some number of trees have been fit.

From bagging to random forests

The above procedure describes the original bagging algorithm for trees. Random forests differ in only one way from this general scheme: they use a modified tree learning algorithm that selects, at each candidate split in the learning process, a random subset of the features. This process is sometimes called "feature bagging". The reason for doing this is the correlation of the trees in an ordinary bootstrap sample: if one or a few features are very strong predictors for the response variable (target output), these features will be selected in many of the B trees, causing them to become correlated. An analysis of how bagging and random subspace projection contribute to accuracy gains under different conditions is given by Ho.

Typically, for a classification problem with p features, √p (rounded down) features are used in each split. For regression problems the inventors recommend p/3 (rounded down) with a minimum node size of 5 as the default. In practice the best values for these parameters will depend on the problem, and they should be treated as tuning parameters.

Adding one further step of randomization yields extremely randomized trees, or ExtraTrees. While similar to ordinary random forests in that they are an ensemble of individual trees, there are two main differences: first, each tree is trained using the whole learning sample (rather than a bootstrap sample), and second, the top-down splitting in the tree learner is randomized. Instead of computing the locally optimal cut-point for each feature under consideration (based on, e.g., information gain or the Gini impurity), a random cut-point is selected. This value is selected from a uniform distribution within the feature's empirical range (in the tree's training set). Then, of all the randomly generated splits, the split that yields the highest score is chosen to split the node. Similar to ordinary random forests, the number of randomly selected features to be considered at each node can be specified. Default values for this parameter are {\displaystyle {\sqrt {p}}} for classification and {\displaystyle p}

for classification and {\displaystyle p} for regression, where {\displaystyle p}

for regression, where {\displaystyle p} is the number of features in the model.

is the number of features in the model.